Found this on LostVault.com (see link on this page). From the Washington Post 7/20/06. If anyone is upset or offended, they should be. Remember, this can happen here.... When this act of relgious violence occured, human rights groups implored the Bush administration including Condolezza Rice to make a statement denouncing this. NOT A FUCKING WORD FROM THEM.

Remember Mahmoud Asgari and Ayez Marhoni murdered for being gay July 19, 2005.

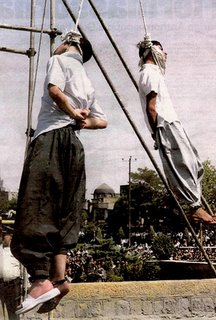

Not since they confronted snapshots of a slightly built young man named Matthew Shepard and the fence where he was left for dead in 1998 by two drug-addled no-hopers in Laramie, Wyo., have gay people been so agitated by a set of photographic images. Protesters brought black-and-white reproductions of the pictures -- which show the public execution last year of two teenage boys in Iran -- to a rally in Dupont Circle yesterday afternoon. The images were also used in other protests, at least 26 in countries around the world, according to bloggers involved in organizing them, and the images are displayed in the windows of Lambda Rising bookstore, near Dupont Circle.

The pictures show a dismally sad drama: Two young men, identified by the Associated Press as aged 16 and 18, are seen shackled in a prison van, sobbing; one of them is then seen being led to a scaffold; other shots show the boys together with dark-hooded men placing nooses around the boys' necks; and two final images show their bodies hanging from ropes, in a large public square, as a crowd watches from a distance.

The hanging images, taken in the large northeastern city of Mashhad, raced across the Internet after the July 19, 2005, execution was reported by the Iranian Student News Association. There was a brief burst of very angry reaction among gay rights leaders, politicians in Europe and some human rights groups in the United States and abroad. Shirin Ebadi, the Iranian woman who won the Nobel Peace Prize for her human rights work, protested the execution of minors. The two boys quickly became gay martyrs, killed, said activists, only because they desired each other and acted on that desire.

But as human rights groups looked into the initial Iranian accounts, the waters muddied. The boys, identified as Ayaz Marhoni and Mahmoud Asgari, were said to have been convicted not for homosexual conduct but for raping a 13-year-old boy. Gay journalists, writing on blogs, cited sources in Iran who said that claim was a smoke screen used by the Iranian government to deflect outrage over the execution. One account, again based on unnamed sources in Iran, suggested that a group of boys had been involved in consensual sexual activity and that the youngest of them (or members of his family) may have claimed he was coerced to avoid trouble for himself. In a country where an accusation of homosexuality is certain to bring harassment, often brings brings prison and torture, and occasionally brings death (by stoning, hanging, bisection with a sword or being dropped from a height, say gay rights groups), that scenario is plausible.

Scott Long of Human Rights Watch says that even a year later international groups know "very little" about what happened. The images are horrifying enough, he says, even if the boys were guilty of rape. And his group has documented plenty of "horror stories," including executions, that have been visited on people caught in same-sex activity in Iran. But can his group say anything about the rape charges?

"Nobody should trust the Iranian government on its face, but we can't document that," he says by phone from his office in New York.

Perhaps the saddest thing about these pictures is that no major news organization outside Iran has tracked down what really happened. The final indignity of these boys' short lives was that they didn't matter enough to spark a serious investigation. And yet, even with the particular facts of the alleged crimes in dispute, the images have haunted gay people in the West and become part of a larger debate about the political alignment of gay rights groups. Should Western activists engage with gay rights issues across cultural and religious borders? And do they risk being dragged into a crude anti-Islamic fervor popular among some fundamentalist Christians (who are no friends to gay people) and right-wing political groups?

Rob Anderson, 23, organized the Dupont Circle protest of about 40 people. He is a researcher and reporter for the New Republic, and he describes himself as part of a "network of lefty friends" who have no interest in the idea of war with Iran. But when the images of the hangings went up last year on the Internet, he printed them out and put them up near his desk. He says that all the friends he's shown the pictures to have had "a shift in consciousness," a realization that they live sheltered lives, that evil exists in the world and that despite the vast cultural difference between Iran and the United States, there have to be moral absolutes. And killing children for homosexuality is one thing that is absolutely wrong.

Over the past year, the ambiguity about why the boys were hanged has mostly faded from discussions on gay Web sites. Gay conservative blogger Andrew Sullivan, who organized a protest in Provincetown, Mass., yesterday, referred to the boys recently as "two gay teenage lovers." A Romeo and Juliet glow has come upon them, two young people killed because of the cruelty and ignorance of an unjust world. As the two boys have taken on iconic status, the cultural difference between them and the rest of the gay world has evaporated. When Anderson looks at the pictures, he feels a powerful connection with the young men.

"For gay people, I think all of us have a fear of being killed, and of being killed for who we are," he says. What he sees is two young men being "executed for something you see in yourself."

The force of the images, for many gay people, has cut through any doubt about their particular meaning. Even if these boys were guilty of rape, there is no doubt that others have been killed simply for being gay. So the pictures are not so much forensic documents as they are dramatizations of something that almost certainly exists. And their power is undeniable.

Images of people who are about to die tell us little about what we really want to know: What is death? How do you pass into it? Is it fearful? And so, unable to learn about death, we query the photograph itself, down to its most mundane details. Looking at these boys, you wonder who brought them the clean white shirts in which they were killed. It seems the sort of thing a mother might attend to. And what of the man, said to be a journalist, who is interviewing them in the police wagon as they cry? Does he sleep at night? And the sandal that has fallen from one boy's foot as he swings on the rope -- did anyone collect it afterward?

Although they have circulated widely on the Internet and were printed in some European newspapers, as well as the New York Times, the images have not been seen in most newspapers here. There is nothing in the pictures taken before the execution that contains blood, or explicit violence, or nudity, the usual taboos of imagery in the United States. And yet something about them is so deeply disturbing that they have had little mainstream circulation.

It is, perhaps, the very blunt and painful confrontation with homophobia that they force upon any viewer who chooses to believe that these are, indeed, images of youth executed merely for being gay. Rarely is the hatred of homosexuals, which flourishes within many of the world's fundamentalist religions, seen so starkly. If the Old Testament, a font of three of the world's major faiths, is the inerrant Word of God, then why should these images trouble you? For God, in Leviticus, says that the killing of homosexuals is justice and pleasing to him.

But if the images trouble the conscience nonetheless, then the viewer finds himself in exactly the position of every gay person who has wrestled with traditional morality and its often harsh absolutes. You find within yourself a moral consciousness that is wider than the wellspring of ancient religion. It is a dizzying sensation of liberation, and its power pulses through every line written by Walt Whitman. But it is, for many, a terrifying thought, and so images are suppressed. And the wasted lives of two young men are ignored by all except those who, through the strange ether of the Internet, feel a powerful kinship with them.

© 2006 The Washington Post Company

_________________

2 comments:

Keep up the good work. thnx!

»

Interesting website with a lot of resources and detailed explanations.

»

Post a Comment